As the most significant worldwide forced migration since World War II, the “Syrian refugee crisis” has been widely covered in media and cinema, though the human dimension has often been lost in statistics or real footage of massive deaths. That’s what makes the short documentary the Refuge Project stand out in its approach to the topic, as it tries to present the crisis through the eyes of refugees from Greek Refugee Camps. Produced and directed by Matthew K. Firpo, and international team of filmmakers who spent four weeks on location on Lesvos Island, Greece, the Refuge project is an observational documentary based exclusively on real-life experience, with no commentaries, and no reenactments, sending the audience a unique and powerful message of what it means to be a refugee.

The film won six awards for Best Short Documentary and got to the official selection of thirteen international film-festivals. It was developed as an independent project funded by Firpo’s company Magna Carta, but at a later stage, many NGOs have been distributing it for free to raise awareness of refugees’ problems.

The Refuge Project is a typical instance of an observational documentary based on the genre’s four leading principles: to record, to promote, to interrogate, and to express (M.Renov, 1993, p.21). By definition, it is not an analytical presentation of events and is also referred to as “cinema verité” or “fly-on-the-wall” type of a movie (B. Nichols, 2001, p.130). Cinema Verité shows people in a real environment with authentic dialogue and natural action. This format excludes the Voice-of-God as a tool of persuasion. The director only observes the characters and leaves it to the audience to make its conclusions. Firpo gives refugees a chance to tell their stories the way they feel it. He just asked them to share and then listened.

Production

In January 2016, Firpo led his team to Greece- the front line of the refugee crisis. “I wanted to point at the fact that every refugee is a human being with hopes, and losses, and family. Moreover, by sharing their stories, I want the audience to see what it means to leave behind everything you know,” said Firpo in our interview. In his attempt to be as realistic as possible, he traces refugees’ every step to safety: from the debarking of smugglers’ boats on the Greek beaches to the camps. Firpo lived in four refugee camps for four weeks and captured every moment of their life.

The Subjects

During their stay at the camps, Firpo and the crew spoke with hundreds of people asking them to share their stories. “The way we conducted the interviews played a part in the intimacy of the finished film. We wanted to divorce our subjects from their contexts and focus on individuals, not on refugee camps. This was not about wide-shots of dirty refugee camps. It was about the humanity of the individual.”

He chose to include twelve personal stories in his film, each of which provides a piece to a puzzle that builds the picture of horror in Syria. The order of appearance of the subjects

focus public attention on two consecutive things: 1) what happened in Syria and how it impacted these people 2) what are their hopes for the future.

Thus, one of the interviews is with Sanah, who speaks of how people were forced to pledge loyalty to either ISIS or Assad, dragging them into the war.

Adam, whose brother was a volunteer who helped the victims of bombing attacks, remembers the “good people” who died in Syria.

Quosay-Sharif shares his horrifying experience of a bombing that went in front of his house and killed his whole family.

Interviews show people from all walks of life, with different experiences and backgrounds, but still sharing one fate.

The Interviews

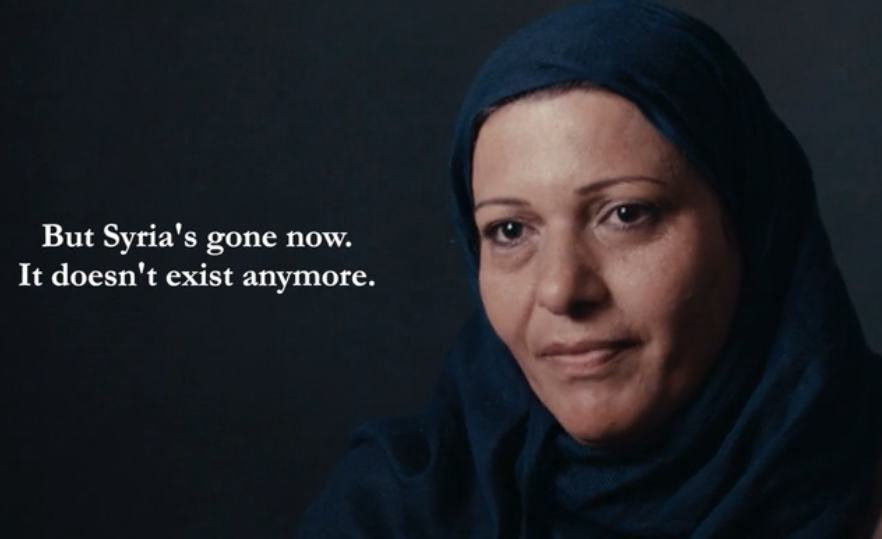

As Firpo puts it: “…the power of these interviews comes from the rawness of the refugees’ wounds.” The interviews are taped before a grey wall; that way, the viewer’s attention is not distracted by any objects in the background. The background is dark, and so are the stories. The realism is almost absolute as there is no makeup, no prep-interviews, no scripts. People’s faces are illuminated from the left so that the shadows outline all traces of suffering on their faces. The subject appears before the camera completely natural, every tear is visible, and every wrinkle or scar is featured. That technique helps place the emphasis directly on the subject’s physical appearance, and what it is an evidence of.

The capture is framed in portrait size, so the viewer concentrates only on the subject’s face — except for the interviews with Hamad and Reem. After Hamad shares how terrified he was and prayed for a quick death, he smiles with relief. The camera switches to widescreen, and we see the Hamad is in a wheel-chair. Reem tells about the bombings in her home-town and how horrified she was. The camera switches to widescreen again- Reem is pregnant; she went through this horror bearing her baby. The change of cut is a technique that is used to surprise the public. First, we see the typical framing, but when it changes, there is a whole other story in focus. By adding more context and depth to the personal details, the director makes us “feel” their pain.

Postproduction

The film shows different aspects of refugees’ day-to-day life in the camps and on the streets of Lesvos. It is a collage of moments of hope, sadness, love, and fear. The camera caught close-ups of refugees – men, women, and children – who were both desperate and hopeful. Multiple shots of their first reactions after stepping on the shore, of the boats, and their life vests amplify the sense of salvation– of Refuge (the title of the film).

All the interviews are in Arabic, but Firpo chose to use subtitles instead of a voice-over. No actor or actress could interpret the pain in these people’s voices. The director’s main priority is to give them a voice, and this is what he literally does. Firpo says that it was essential to follow the subjects’ eyes and expressions at all times, so he put the subtitles next to the speaker’s head. That way, viewers would not look down to the subtitles and back up to the interviewee. “We wanted to allow audiences to entirely focus on the stories being told: faces, eyes, mannerisms, and to enter into this kind of intimate conversation with another person without being taken out of that moment,” explained the director.

On-screen context

Firpo included small portions of additional information in between the interviews. Text appears on the screen informing the viewer about the time and place the interviews were taken, the number of refugees in the EU at that point, the places of the most devastating bombings in Syria. These are beneficial to the otherwise observational format of the film because the statistics provide viewers with contextual references. The information is crucial because it shows the scale of the tragedy. I believe that if there had been more pieces of data or just raw facts of the kind, the film would have been even more powerful. The public relates to numbers, so if in addition to the personal stories Firpo had provided the number of children that had crossed the sea, the number of destroyed homes in Syria, or the number of people hosting refugees, etc. ( information is available at The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ website), it would have provided additional depth to the film as these data give factual dimensions of the crisis that enhance the personal stories.

Epilogue. Takeaways.

The Refuge Project is an emotional snapshot of Syrian refugees’ fate. It uses the power of the observational documentaries to capture raw moments of their life. Firpo builds the movie on personal stories without imposing his personal opinion, avoiding showing refugee camp conditions. I think this is the most powerful tool Firpo uses—neutrality. He leaves it to the viewers to make their judgments. Given the gravity of the refugee crisis, it is pivotal that the film does not try to influence the public directly; it is a witness testimony, whose primary purpose is to tell personal stories about the Syrian war. The realism of the interviewee’s face is a vivid enough illustration of the horror. The use of official data showing the magnitude of the refugee wave, I think, would benefit the credibility of the narrative and strengthen the interviewees’ stories. It could have been an additional tool to enhance the viewers’ experience of the movie. However, “Refuge” ‘s strength lies precisely in its being a glimpse at the destruction of human life and the eternal hope for a new beginning.